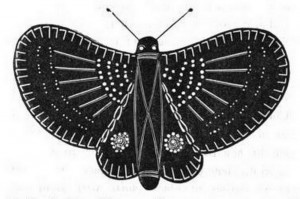

Pen wipers have been used in some form since pen and ink were first put to paper. They are used for cleaning ink from dip and fountain pen nibs. Early in their history, pen wipers were simply pieces of fabric, often felt, even buck skin or whatever else may have been available; The Teacher’s Assistant published in 1859 offers the penmanship rule of never wiping your pen in your hair.[1] Nathaniel Hawthorne used his writing robe to wipe his pens; his wife eventually made a cloth butterfly shaped pen wiper and attached it to the robe to hide the ink stains and then eventually made him a new robe.[2]

Pen wipers have been used in some form since pen and ink were first put to paper. They are used for cleaning ink from dip and fountain pen nibs. Early in their history, pen wipers were simply pieces of fabric, often felt, even buck skin or whatever else may have been available; The Teacher’s Assistant published in 1859 offers the penmanship rule of never wiping your pen in your hair.[1] Nathaniel Hawthorne used his writing robe to wipe his pens; his wife eventually made a cloth butterfly shaped pen wiper and attached it to the robe to hide the ink stains and then eventually made him a new robe.[2]

Pen wipers were considered a necessity during the 19th century. Darwin made sure not to forget his and included it on his list of things to take on a visit to a spa in 1859.[3] Manuals for teachers and annual school reports frequently mention that pen wipers were either supplied to their students or that the students supplied their own. Pen wipers were common-place enough in 19th century material culture to be frequently mentioned in novels; not as something spectacular but as an ordinary accoutrement of a writing desk or an acceptable gift to give a friend or acquaintance.

Because they were so common, pen wipers were frequently used to promote ideas and agendas, similar to our promotional note pads, bumper stickers or magnates. One example is the pen wipers inscribed with “Wipe out the blot of Slavery” and “Plead the cause with thy Pen” available at an anti-slavery fair held in Pennsylvania in 1836.[4]

While many pen wipers were made at home or through cottage industries, at least one company in London made them commercially early in the century. The J. K. Farnell Company began business in 1840 making pen wipers, tea cozies and pin cushions; today they manufacture teddy bears. Later in the 19th century, English silver company Sampson Mordan & Co. produced pen wipers topped with silver and gold animals, in the shape of boot scrapers, or simple, round, silver-framed doomed brushes.

As the middle class rose in the 19th century, pen wipers became one of several

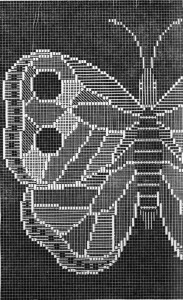

As the middle class rose in the 19th century, pen wipers became one of several  items offered to women with time on their hands to show off their handiwork skills. No longer was a simple piece of fabric used as a pen wiper; they were now ornamental. They were knitted, crocheted, beaded and embroidered. They could be a simple geometric shape or shaped as animals or insects. Butterflies seemed to be very popular as a shape for pen wipers.

items offered to women with time on their hands to show off their handiwork skills. No longer was a simple piece of fabric used as a pen wiper; they were now ornamental. They were knitted, crocheted, beaded and embroidered. They could be a simple geometric shape or shaped as animals or insects. Butterflies seemed to be very popular as a shape for pen wipers.

Jus t about every woman’s magazine or household advice book contained at least one pattern or set of instructions for a pen wiper. Girls were encouraged through activity books to make pen wipers as intricate as those suggested in the women’s magazines or whimsical ones such as those made of dolls.

t about every woman’s magazine or household advice book contained at least one pattern or set of instructions for a pen wiper. Girls were encouraged through activity books to make pen wipers as intricate as those suggested in the women’s magazines or whimsical ones such as those made of dolls.

Ornamental pen wipers still had not lost all their practicality. In The Girl’s Own Book, Lydia Child admonishes that pen wipers or at least the part that actually wipes the pen, should “always be made of black flannel or broadcloth: other colours soon get spoiled by the ink.”[5] This same advice is repeated in 1860 almost verbatim by Ebenezer and Alice Landells in The Girl’s Own Toy-maker and Book of Recreation.[6] The majority of the patterns and instructions that I found called for some type of black cloth to be used for the wiping cloth.

Once these ornamental pen wipers were completed, they were frequently given as gifts, donated to charity bazaars or remained in the household as useful decorations. A bazaar held in 1863 in Rochester, New York for the Ladies Hospital Relief Society had several pen wipers for sale including “doll’s pen wipers”, “mosaic pen wipers” and “butterfly pen wipers”. Some of these donations were from men but it is not possible to determine if they actually made the wipers or if they had donated the work of women.[7] John Henry Newman best describes the double use of these ornate pen wipers in a letter written in 1855 regarding a gift of a pen wiper: “A pen wiper is always useful. It lies on the table, and one can’t help looking at it.”[8]

Pen wipers continued to be a necessity through the mid-20th century as long as dip and fountain pens were the primary writing instruments. While still used today by persons who use dip and fountain pens, pen wipers are no longer considered a necessity by the general public and cannot be generally found in stores or patterns for them found in magazines.

My Penwiper

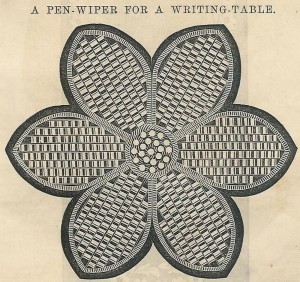

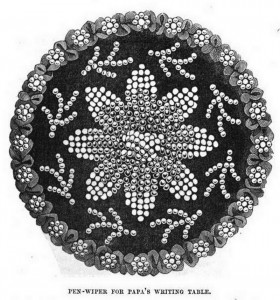

I based my pen wiper on a pattern for a “Pen-Wiper for a Writing Table” in the March 1860 edition of Godey’s Lady’s Book, pages 263-264. This pen wiper is beaded and uses what the pattern calls cross-stitch. I have listed the materials called for in the original pattern and the materials I used in my pen wiper. I do not use the camel hair brush or the ink and sugar in tracing and drawing the pattern; I used a modern colored pencil to trace the pattern and to transfer the pattern to the canvas.

Number 20 cotton

This is used to sew the beads down on the pen wiper. I used 100% cotton 20 weight crochet thread. It is about the same size as upholstery thread.

Penelope canvas, which measures nine double threads to the inch.

This was not available in my area. I ordered the canvas from Needle in a Haystack in California. The canvas is 100% cotton Penelope double mesh, 10 count, manufactured by Zweigart.

Bright green Berlin wool

This refers to the weight of yarn that would be used for a style of embroidery known as Berlin work, so named due to the development of the patterns (not the yard) in Berlin, Germany. I used green three ply Paternayan brand 100% wool yarn.

Thick, short white bugles

These were hard to find. Bugle beads are fairly common but not in a size I thought reflected “thick and short” in a material appropriate to the 19th century. At a local bead store that specializes in vintage beads, I found strands of 1920s translucent white glass bugles of the size and shape I felt were appropriate.

Large sized white chalk beads

Again, difficult to locate in my area. After a search on the internet to determine exactly what “chalk” beads looked like, I did find some glass beads that had a similar look. However, I did not like the effect with the 1920 translucent beads. I used a smaller, more translucent white glass bead instead.

Scarlet cotton velvet, merino or cloth

I used red 100% cotton velveteen.

Black stuff cut into circles

I used plain 100% cotton broadcloth

Gum-water

I mixed the gum water using gum Arabic powder from a local herb store. The recipe I used is from MacKenzie’s Five Thousand Receipts published in 1854.

In my research I found that gum-water was used in making ink or paints at home, for stiffening fabrics and in medicines in addition to glues and pastes. Most mentions of gum-water simply state “mix with gum-water or “use light gum-water”, but there are few instructions to tell you how to make the gum-water. One can assume that it was commonly used and that mixing instructions were not needed. When it came to gluing the velvet to the beaded part, I had to add more gum Arabic to the water to make a thicker mixture, more the appearance of oil as described in another recipe that also included mixing in starch for stiffening.

Process Photos

“With green wool and a rug needle work, or run the outline round, and then overcast the running, exactly as if it were muslin instead of canvas; this overcastting must be thickly and finely worked by separating the double stitches of canvas. The centre circle is filled up in cross-stitch…”

“With green wool and a rug needle work, or run the outline round, and then overcast the running, exactly as if it were muslin instead of canvas; this overcastting must be thickly and finely worked by separating the double stitches of canvas. The centre circle is filled up in cross-stitch…”

“…and the chalk beads sewed on this. For the bugles.—These must lie across the stitch of canvas, all one way, and be sewed on with cotton doubled, beginning at the point of the leaf; bring the cotton through as if for single cross-stitch, thread on a bugle, slip it down, pass the needle down through the canvas on the top of the stitch. Each row must be commenced at the same side as the first row: that is, when one row is finished, slip the needle under and back to the bottom of the next ditto under the first row…” I did not like the look of the pen wiper beaded in this way as it left gaps between some of the beads and the overcast edge. Perhaps it is to allow the velvet to poke through; however, I found that the white canvas threads showed as well and were too much of a contrast with the velvet and was distracting. I, therefore, filled the leaves with the beads rather than follow the pattern verbatim.

“…and the chalk beads sewed on this. For the bugles.—These must lie across the stitch of canvas, all one way, and be sewed on with cotton doubled, beginning at the point of the leaf; bring the cotton through as if for single cross-stitch, thread on a bugle, slip it down, pass the needle down through the canvas on the top of the stitch. Each row must be commenced at the same side as the first row: that is, when one row is finished, slip the needle under and back to the bottom of the next ditto under the first row…” I did not like the look of the pen wiper beaded in this way as it left gaps between some of the beads and the overcast edge. Perhaps it is to allow the velvet to poke through; however, I found that the white canvas threads showed as well and were too much of a contrast with the velvet and was distracting. I, therefore, filled the leaves with the beads rather than follow the pattern verbatim.

“…when all the bugles are sewed on, stretch it with the bugled side downwards on a table with five or six tin tacks; then well gum over the work, let it remain till quite dry…”

“…when all the bugles are sewed on, stretch it with the bugled side downwards on a table with five or six tin tacks; then well gum over the work, let it remain till quite dry…”

“…then cut away the canvas close to the overcasting so that not a particle of the canvas can be seen…”

“…then cut away the canvas close to the overcasting so that not a particle of the canvas can be seen…”

“…gum the back of the star again, lay it on the right side of the velvet, and place a heavy weight on it till dry.”

“…gum the back of the star again, lay it on the right side of the velvet, and place a heavy weight on it till dry.”

This took a bit of experimentation with the gum water proportions. It also took about 3 days to dry.

“When cut, leave the velvet about half a quarter of an inch beyond the green outlines.”

“When cut, leave the velvet about half a quarter of an inch beyond the green outlines.”

“Cut some circles of cloth, so that they do not project so as to be seen, and sew them through the centre of the star.”

“Cut some circles of cloth, so that they do not project so as to be seen, and sew them through the centre of the star.”

Conclusion

This was a relatively easy item to make in the 19th century, using skills that most middle-class women would have known with supplies easily obtainable. But in the 21st century following this pattern required not so much sewing skill as research skill. Determining and locating the appropriate materials was a task most women in the 19th century would not have had to face.

The project re-emphasized for me the difference in knowledge between now and the mid-19th century specifically in dealing with the gum water. It is something we no longer use on a regular basis and probably most of the population would not know what it is or for what it can be used; however, it was quite common in a 19th century household, common enough that only the most basic instructions were offered as to how to produce it. The canvas required was also something not readily available to me at thread shops as double thread canvas has been replaced by mono canvas in today’s canvas work.

It also illustrated the middle class experience at the middle of the 19th century. This project took me about one month to complete. Even though I work a full time job, I have appliances and prepared foods to speed my cooking and more appliances to do my laundry. I have electricity to provide heat and good lighting (a necessity with the small beads and old eyes). A woman in the 19th century who expected to complete this pen wiper would have had to have the resources to supply the household help needed to leave her the free time to work on it. It is quite evident for whom these patterns, and the books and magazines that contained them, were written.

[1] Northend, Charles. The Teacher’s Assistant: Or Hints and Methods in School Discipline and Instruction; being A Series of Familiar Letters to One Entering Upon the Teacher’s Work. (Boston: Crosby, Nicholas, and Company, 1859) 180.

[2] Hawthorne, Julian. Nathaniel Hawthorne and His Wife, Volume I. Chapter 7. http://www.eldritchpress.org/nh/nhahw107.html

[3] The Complete Works of Charles Darwin Online. “Things for a week” page 1. http://darwin-online.org.uk/content/frameset?itemID=CUL-DAR210.9.30&viewtype=text&pageseq=1

[4] The Liberator. (Boston: William Lloyd Garrison and Isaac Knapp, January 2, 1837.)

[5] Child, Lydia Maria Francis. The Girl’s Own Book. (London: William Tegg & Co, 1856) 319.

[6] Landells, Ebenezer, Alice. The Girl’s Own Toy-Maker and Book of Recreation. (London: Griffin & Farren, 1860)117-118.

[7] Report of the Christmas Bazaar Held Under the Auspice of the Ladies Hospital Relief Association Dec. 14-22, 1863. (Rochester: Benton & Andrews, Book and Job Printers, 1864).

[8] Ward, Wilfrid. Life of Cardinal Newman, Volumes 1 and 2. (New York: Longmans, Green & Co. 1912). 312

[9] An American Physician. MacKenzie’s Five Thousand Receipts In All the Useful and Domestic Arts. (Philadelphia: Hayes & Zell, 1854) 53.

Bibliography

A Lady. The Workwoman’s Guide. Simpkin, Marshall, & Co., London, 1840.

A New Collection of Genuine Receipts. Charles Gaylord, Boston, 1831.

Barnard, Henry. Reports and Documents Relating to the Public Schools of Rhode Island for 1848. Providence, 1849.

Beeton, Isabella, ed. The Book of Household Management. S.O. Beeton, London, 1863.

Child, Lydia Maria Francis, Eliza Leslie. The Little Girl’s Own Book. Robert Martin, Edinburgh, 1847.

______________________ . The Girl’s Own Book. William Tegg & Co., London, 1856.

Collins, William Wilkie. My Miscellanies. Sampson Low, Son & Co., London, 1863.

“Encaustic Painting”. The Saturday Magazine. June 12, 1841.

Hale, Sarah, ed. Godey’s Lady’s Book, March 1860.

Hale, Sarah Josepha. The New Household Receipt Book. H. Long and Brother, New York, 1853.

Hawthorne, Julian. Nathaniel Hawthorne and His Wife, Volume 1. New York, 1884.

How To Do It: Or, Directions for Knowing and Doing Everything Needful. John Tingley, New York, 1864.

Katz, Peter. “Pen Wipers”. Journal of the Writing Equipment Society. Autumn 2000: 14-16.

Lambert, Miss A. The Hand-book of Needlework. Wiley & Putnman, New York, 1842.

Landells, Ebenezer, Alice. The Girl’s Own Toy-Maker, and Book of Recreation. Griffith and Farran, London, 1860.

Leslie, Eliza. Miss Leslie’s Lady’s Housebook. A Hart, late Carey & Hart, Philadelphia, 1850.

Macgowen, J. Florence Egerton or Sunshine and Shadow. William P. Kennedy, Edinburgh, 1854.

MacKenzie, Colin. MacKenzie’s Five Thousand Receipts. Hayes & Zell, Philadelphia, 1854.

Northend, Charles. The Teachers Assistant, or Hints and Methods in School Discipline and Instruction. Crosby, Nichols and Company, Boston, 1859.

Ohio State Teachers Association. The Ohio Educational Monthly. E.E. White, Columbus, 1863.

Parrish, Edward. An Introduction to Practical Pharmacy. Blanchard & Lea, Philadelphia, 1859.

Report of the Christmas Bazaar Held Under the Auspice of the Ladies Hospital Aid Society, From Dec. 14 to Dec. 22, 1863, inclusive at Corinthian Hall, Rochester NY. Benton & Andrews, Book and Job Printers, Rochester, 1864.

The Complete Works of Charles Darwin Online. [Charles Darwin’s] ‘Things for a week’ (5.1859). http://darwin-online.org.uk/content/frameset?itemID=CUL-DAR210.9.30&viewtype=text&pageseq=1

The Illustrated Girl’s Own Treasury. Ward & Lock, London, 1861.

The Liberator, January 2, 1837.

Twenty-First Annual Report of the School Committee of the City of Lowell. Being for the Year Ending December 31, 1846. Joel Taylor, City Printer, Lowell, 1847.

Unknown. The Lady’s Album of Fancy Work for 1850. Project Gutengurg, 2004. http://infomotions.com/etexts/gutenberg/dirs/1/2/6/4/12642/12642.htm

Unknown. The What-Not; or Ladies’ Handy-Book. Piper, Stephenson, & Spence, London, 1859.

Ward, Wilfrid. Life of Cardinal Newman, Volumes 1 and 2. Longmans, Green, and Co. New York, 1912