Patriotism and Necessity: The Use of Homespun in the Southern US

during the American Civil War

Written by Annette Jorgensen, based on the research of Vicki Betts

You can also view a different version of this presentation “A Silk Purse from a Sow’s Ear: Fashioning Homespun in the Mid-19th Century” on the Presentation page.

Chicago Tribune, June 24, 1864. p.3, c.3

Ackworth, Ga., June 9, 1864

Editors Chicago Tribune:

The accompanying song is from a letter of a Southern girl to her lover, in Lee’s army, which letter was obtained from a mail captured on our march through Northern Alabama. The materials of which the dress alluded to is made in cotton and wool, and are woven on the hand-loom, as commonly seen in the houses at the South. The scrap of a dress enclosed in the letter as a sample was of a grey color with a stripe of crimson  and green—quite pretty and creditable to the lady who made it…

and green—quite pretty and creditable to the lady who made it…

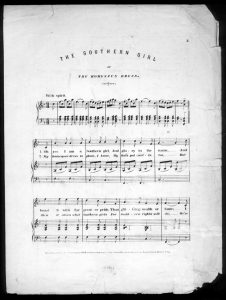

Most scholars of the Civil War home front are probably familiar with the song “The Southern Girl or The Homespun Dress”. Attributed to Carrie Belle Sinclair in 1862, it praises women for wearing homespun dresses in support of the South during the Civil War. The homespun dress has become the symbol of the hard scrabble life many Southerners experienced during the Civil War. But how common was homespun? Was it worn as a sign of pride as suggested by the song or was it worn out of necessity when all other fabric choices were used up?

What is Homespun?

Homespun can be:

- All handspun and hand woven, what most of us think of when we think “homespun”

- Factory spun warp, handspun filler, hand woven

- All factory spun, but hand woven

- All factory spun, and factory woven in the South, where “home” means the South; intended to resemble true hand woven fabric

- Fake homespun—factory spun and woven in the North—considered a cheap imitation

It is impossible to know for sure what kind of homespun is being discussed in sources unless it is specifically mentioned how it was produced.

Making Homespun

Home spinning and weaving had fallen out of common practice by the time of the Civil War; diaries and newspapers often mention taking spinning wheels out of the attic, or of women having to learn to spin and weave. However, some women were producing homespun for home and retail purposes.

Between 1915 and 1922, 200 Tennessee Confederate veterans responded to a state survey, with 182 answering the following question:

State clearly what the duties of your mother were. State all the kinds of work done in the house as well as you can remember—that is, cooking, spinning, weaving, etc.

Of those 182, the following results were tabulated for textile production:

| Spun | Dyed | Wove | Carded | |

| Number | 128 | 1 | 126 | 22 |

| Percentage | 70.3 | .55 | 69.2 | 12.08 |

In addition, 11 veterans (6.04%) stated that their mothers superintended slaves who spun and wove.[1]

Mary Love Fleming remembered in Dale County Alabama “At first few knew how to spin and weave. But my aunt, Mrs. Bennett, and some of the older women in the Byrd, Martin, and Johnson families had learned to spin and weave long years before, and they now gladly taught relatives and all others who wished to learn. Women from all over that section of the country went to them to learn how to manage the spinning wheels and the looms.”[2]

Kate Cummings writes from Georgia in 1862 “This lady had two young daughters, who were busy weaving and spinning. They had on dresses spun and woven by themselves. This ancient work is all the fashion now, as we are blockaded and can get no other kinds of goods.”[3]

Diaries of the planter class in the south often give the impression that plantation mistresses produced multitudes of cloth and thread. In her letters to her husband, Harriet Perry mentions several times the amount of cloth her mother-in-law has managed to spin. In 1862 she writes “the spinning machine spins thirteen yards of cloth per day-they have two looms weaving now.”[4] By October she is making 90 yards of cloth a week and by February 1863 she had made nearly two thousand yards of cloth.

As often as Harriett mentions her mother-in-law making cloth you would think she was a very busy woman, skilled in spinning and weaving; however, it is the enslaved persons of the plantation doing the work, male and female. Harriett comments that Aunt Betsy, an enslaved woman, is with the looms all the time. Also, Willis and two women spin from light till dark. Willis and the two women “spin the warp for fifteen yards every day”[5] and the “women, who have young babies are spinning with the hand.”[6]

Making a completely homespun/homemade dress is time consuming; taking more time than the typical white woman in the 19th century was willing to devote to clothing production without help.

W.N. Watt, in Early Cotton Factories in North Carolina and Alexander County estimated that it took 360 hours to produce 30 yards of homespun fabric—

- 160 hours to pull the cotton by hand from the seed and card it when cards were available. The manufacturing of cards became less of a priority once the war began. The cost of cards when they could be bought went for $10 to $80 a pair.

- 85 hours to spin and then hank the weft

- 17 hours to gather bark, dye, size the thread and spool the warp

- 12 hours to quill the weft

- 10 hours to warp, beam, harness and “slew” the loom

- 75 hours to weave the cloth

A total of 36 work days of 10 hours each. If the labor is proportionate, it should take almost seven 10-hour days to produce the 5 2/3 yard of cloth for the Furr dress currently owned by Vicki Betts. [7] (http://apps.uttyler.edu/vbetts/furr_homespun_dress.htm)

Betty J. Mills, in Calico Chronicle, estimated that it took two weeks to spin the thread for a dress, one week to weave, and another week to cut and hand sew a dress, depending on the complexity.[8]

Just a piece of trivia: Using 36 threads per inch, 34″ wide and 5 2/3 yards long, there is roughly 498,804 inches of weaving thread in this length of fabric, or 41,567 feet, which is close to 7.87 miles

Dyeing

In addition to the production of the thread and cloth, there was dyeing, either of the thread or the cloth. There are many people much more knowledgeable on dyeing then I, so I will leave the details of that topic for another time. However, I will share a few items outside the process discussion.

“The ladies down south they do not denigh

They used to drink the coffey and now they drink the rye

The ladies in dixey they are quite in the dark

They used to bye the indigo and now they bile de Bark.”

–a poetic taunt of a Yankee passed on by a North Carolina soldier in 1864[9]

Most Commonly Mentioned Southern Dyes, 1861-1865

Walnut (Hulls, Leaves, Bark)

Indigo (Cultivated or Wild)

Black Oak

Sassafras

Hickory

Maple

Logwood

Mordants

Copperas/Iron

Alum

Lye

Fannie Brown of Rusk County Texas entered instructions in her diary:

To dye Brown

Take the bark of the root of the common wild plumb, boil untill [sic] the dye looks almost black

Strain and add a small quantity of copperas dissolved in a small quantity of lye

Take the root of the broom straw layer a layer, a layer of cotton, a layer of the root then of cotton till the pot is full, sprinkle on salt, fill the pot with water, boil well, it will be a pretty red.

Upland Huckelberry [sic] will dye a blue, cotton

Wild indigo will dye cotton a yellow, saturate blue stone, then put the dyed yellow cotton in a layer and dye, it will be green[10]

The Confederate government even published instructions on dyeing.

Purchasing homespun

Purchasing homespun was an option if one did not want to go through the work of making it. The Perrys sold the cloth produced on their plantation at a rate from 100 to 125 dollars a week; it is unclear who is buying the cloth. Based on the amounts, probably the government or other slave owners purchasing slave cloth. And even with all this cloth on hand, they are still purchasing calico on the market.

Harriet also mentions in 1862 “everyone is very busy making cloth & there is a good deal for sale at $1 & 1.25 per yard for common plain negro cloth…”[11]

Prices for homespun differed greatly by year of the war and location in the South. For example, in 1862 Southerns could find homespun from 50 cents to 4.00 a yard depending on where in the south they were. By 1865 the cost had risen to 8-10 dollars a yard. Calico, on the other hand, in 1862 cost between .50 and $2.00 a yard and by 1865 ranged from $25-35 a yard.

M.J. Pierson of Lamar County TX wrote to Mrs. Winstead in November 1863 “I have sold some cloth at a dollar and half a yard…”[12]

The Southern Illustrated News, published a letter from Louise November 8, 1862 “Well, Messrs. Editors, I bought me a home-spun dress, had it made up and wore it to church on Sunday last.”[13]

It is important to pay attention to this quote: She bought a homespun dress, meaning she bought enough fabric to make a dress and had it made up. It is unknown if she made it or someone made the dress for her or where she bought the fabric. The important information is that she bought the fabric, she did not make it.

Since homespun was so labor intensive and, obviously, early in the war other options were available, why was it being used in fashion? Early in the war it appeared as a patriotic statement. Homespun as a patriotic statement dates back prior to the Revolution. It served to promote American industry, simplicity, and democracy as opposed to “British luxury and corruption.”

As tensions rose in 1860 and 1861, Southerners again turned to the old symbol, fully aware of homespun’s historical significance. While across Virginia, in late 1859, men met and spoke on self-dependence, by early 1860 “the ladies have begun to act. Without noise they have commenced to give force and color to our resolutions” by sponsoring homespun parties. “More than a hundred ladies and gentlemen, belonging to the most respected families in the city [Richmond], were present all of whom were attired in part or in whole in garments of homespun”.[14]

Elzey Hay from Georgia remembered in 1866:

“In the first burst of our ‘patriotic’ enthusiasm, we started a fashion which it would have been wise to keep up. We were going to encourage home manufacture—we would develop our own resources, so we bought homespun dresses, had them fashionably made, and wore them instead of ‘outlandish finery.’ The soldiers praised our spirit and vowed that we looked prettier in homespun than other women in silk and velvet. A word from them was enough to seal the triumph of homespun gowns.”[15]

Caroline Seabury wrote in her diary while in Mississippi in 1863 “Then they showed me cloths they had spun and woven of themselves—saying ‘I’ll wear homespun as long as I live before I’d depend on Yankees for it…’” [16]

“The people were wild with the ‘non-consumption’ craze, going back to homespun jeans, lye soap, etc., long before the necessity was upon us.” Remembered Elizabeth Lyle Saxton[17].

Homespun truly became a fashion. Per Clara Dunlap from Arkansas in 1862 “. . . it does seem right diverting now Ma, to go visiting, & hear everyone discussing the merits of this, that, or other mode of dying, & how many cuts of such & such a No. it takes to fill a yd of such a No. & cc & so on, but aint [sic] it so different from a few years since, when all the topic under discussion would be fashion’s, & cc…”[18]

Schools also encouraged homespun. In October of 1860, twenty-seven teachers and pupils of the Spring Hill School attended the Georgia State Fair “all attired in a substantial Check Homespun Dress, made fashionably full and flowing” “a sight worth seeing on a southern fair ground.” One of the students, Sarah Conley Clayton later wrote about the experience.

According to her “to show our patriotism at that critical time, we were all clad in homespun dresses made by our own hands, the girls, with two or three exceptions being under sixteen years of age. We were a proud set, and were confident of being the first to appear in Georgia cotton; so in our simply made blue and white and brown checks, with all eyes upon us we walked proudly from the Union Depot out to the grounds on Fair Street near the cemetery.”[19]

The girls did win a prize, but they were “a little bit crest fallen” to discover another homespun clad young lady also in attendance. Years later Sarah could describe almost every detail: “In her dress, a clear, bright blue was the predominating color; a narrow buff stripe, with probably a red and white thread running through it, alternating with the blue about every half inch. It was made quite stylishly, as I remember; more of a riding habit, a pretty skirt and tight coat piped with buff and ornamented with numerous buttons, we understood that she herself had woven the material.”[20]

Graduating classes made a special effort to patronize homespun, much as Harvard and Yale did during the Revolution. In March 1860, the students of Mercer University pledged themselves to buy “no more apparel of Northern manufacture. . . [and] to appear on the rostrum of our next Annual commencement in Southern-made clothing.” During the summer of 1861, an article entitled “Home Spun at the Mary Sharp” announced that the young ladies graduating from this Baptist college in Winchester, Tennessee, had chosen “home made cotton dresses” as their clothing of choice for commencement.[21]

“It was designed to be emblematical of the intention of these young women to make themselves all the present condition of our country may require her daughters to be. We have since heard of some of these graduates appearing at church in the same humble but becoming garb, where it elicited the earnest admiration of the right thinking of the other sex.”[22]

Myrtie Long remembered her cousin Carrie graduating from College Temple in Newnan, Georgia. The class chose homespun for their graduation dresses. “The whole county praised the act. On that day every body [sic] was singing the popular song: ‘Hurrah, Hurrah! For the Southern girls, Hurrah! Hurrah, for the homespun dresses that the Southern Ladies wear!'”[23]

Editors and correspondents noticed particular young ladies around the region who exemplified the Southern ideal. “Home Industry” wrote in to the Charleston Mercury in November 1860:

“We observed, while on a visit to a lady friend, a bonnet and dress of Georgia linsey and cotton, designed for the daughter of one of our leading Secessionists. The dress is made in fashionable style, a la Gabrielle, and the bonnet is composed of white and black Georgia cotton, covered with a net work [sic] of black cotton, the streamers ornamented with Palmetto trees and Lone Stars, embroidered in gold thread, while the feathers are formed of white and black worsted. The entire work is domestic, as well as the material, and exhibits considerable ingenuity. The idea illustrates the patriotism of the ladies, and their earnest sympathy with the great Southern movement, while its execution affords convincing proof of how independent we can be of our Northern aggressors, when we have the will to undertake and the energy to achieve.”[24]

Within the next month, the Columbus [GA] Times noted “In the street yesterday was observed one of our pretty young ladies attired in a dress of Georgia homespun and wearing the blue cockade. The make of the dress and the style of the cloak, gave it the appearance of silk at a distance, and attracted the attention of all.[25]

The year 1861 brought more accolades from the press. “Two of Portsmouth’s (Va.) fair daughters appeared in its streets Tuesday in homespun, and the general verdict was they looked charming.”[26]

The Atlanta Locomotive reported that

“A gay and fashionable young lady attracted the attention on the Fair ground [sic] yesterday, because of a most handsome, and neatly fitting copperas homespun dress, which she wore, and seemed justly proud. She is wealthy of a fine family, and for her dress, which really was among the handsomest of any kind on the ground, she certainly deserves a grand premium, and we insist upon the Agricultural Society awarding her one. We heard a number of ladies wish for a dress like it, but whether they wished it because of the style of the goods, or because they discovered it to be so popular we will not say. But most assuredly we were delighted to see this one Southern lady rigged out in home made [sic] cloth.”[27]

“Miss T.”, the daughter of a friend of the editor of the Atlanta Southern Confederacy, arrived at that printing establishment on August 24, 1861, “dressed in beautiful checked homespun; white, blue, copperas, and ‘Turkey Red’ colors were beautifully woven into the fabric. It really was refreshing. Then it fit right. It was not only spun and wove, but cut and fit by the accomplished wearer, who has just completed a collegiate education. . . .Let us have more homespun dresses—enough at least to destroy the novelty; and let us have more good warm jeans for gentlemen, and for our soldiers to wear this winter.”[28]

By fall, the Charleston Courier was noticing “Many beautiful damsels were seen yesterday on King street, in suits of homespun. We trust the example will be followed, and if our fair ladies know how much pleasure it afforded to the volunteers and to all good citizens, it would be generally and universally followed.”[29]

If editorial comments were not enough, some prominent citizens sponsored “homespun parties” of various sorts and fairs. In Atlanta, Georgia 1861

“Ladies’ Relief Society.

September 24th, 1861.

. . . The Ladies of the ‘Society’ are to have a ‘Fair,’ next Tuesday evening, and hope for the sake of the cause prompting it, to have a full attendance. Tickets for admission 25cts. The ladies will appear in southern homespun.”

And then in Milledgeville, Georgia,

“The ladies of this city, or at least a good many of them, had a homespun party at Newwell’s hall, on last Thursday evening, which was decidedly the most pleasant affair that has occurred in the city for many years. The ladies all wore homespun dresses, and their persons were tastefully and appropriately ornamented with native jewels and charms. Many of the dresses, though of the plainest cotton fabric, were beautiful, and the wearers looked charming in them. . . . [The group was] delighted with the first experiment of a social gathering in plain and unpretending attire. The animus of this party was decidedly secession, but we believe there was perfect union among the company.”[30]

In Leake County, Mississippi, Col. Donald gave a party in which “The ticket sent to each young lady, required that she should come dressed in Mississippi manufactured apparel, in the manufacture of which she must in some way assist. The gentlemen were also required to dress in the manufacture of Mississippi, made in Leake and Attala. There were near one hundred persons of both sexes in attendance, all attired as specified above.”[31] In March 1861, the young ladies of Albany, Georgia, gave a “Homespun Pic Nic.” “We were not present, but learn that a great number of the fashion and beauty of the city were there, and several gentlemen and many of the young ladies dressed in plain but neat Homespun dresses. This is praiseworthy.”[32] In Atlanta, for one of the first Fairs sponsored by the Ladies’ Relief Society in September 1861, the notice in the newspaper announced that “The ladies will appear in southern homespun.”[33]

One of the most interesting accounts, however, is of an Alabama homespun ball. Mrs. Elizabeth Lyle Saxon recalled the preparations leading up to that event and the unintended results.

“The young ladies were all preparing for a grand ball, that was soon to be given, and four of them were going to wear homespun dresses. . . The four girls were sewing on their dresses, vile-smelling, common checked goods, such as we used for our servants at that time. They were making them with long trains, low neck and short sleeves, and the lace they were trimming them with was Pointe de Alencon, Honiton and Valenciennes, suitable for the dress of a duchess at a court ball. . . When the ball came off the girls looked as lovely as when in satin and lace, for the dresses fitted their perfect figures to a charm. One of the young men who had danced with all the four came to me, and taking me to one side, asked in a hollow whisper: ‘Miss Lizzie, what in heaven’s name is it that smells so awfully about those girls?’ ‘Why, it is a new perfume they are using,’ I said. ‘They call it patriotism; I call it indigo dye.’ ‘Oh,’ he said, ‘it is the dresses; why didn’t they wash them? It is a horrid smell.’ I told the girls about it, and when they got home they were a beautiful blue all about their necks, and they hardly allowed the word homespun ever to be uttered to them until we really had to make it at home and wear it.”[34]

The young Southern ladies of 1860 and 1861 created and “ostentatiously” wore their homespun dresses as a means of being “heard” politically, without leaving their separate spheres and without having the vote. Homespun became, for them, a visible tie with their heroic and independent past and a uniform to match the gray of their brothers and beaux. Some soon became disillusioned with the fashion, however, putting their dresses aside when they washed poorly or were too hot to wear.

Giving Up Homespun

Amanda McDowell of White County TN writes in October 1864 “We have got our wool ready. . . at last, Oh! I am getting so tired picking, coloring, carding, spinning, etc., I would secede from it if I could conveniently.”[35]

“Hoops were discarded by some, but upper-class women tended to cling to the billowing skirts for dress occasions; they also made relatively little use of homespun, depending instead on re-made finery of prewar times or on new clothing obtained from outside the South. A young Georgia aristocrat wrote one of her friends in March 1863: “I am going into the [Federal] lines . . . and expect to get the prettiest wardrobe which Paris or France afford. . . . I am so delighted, for really I have not felt lady like for the past two years, my wardrobe has been in such a dilapidated condition.”[36]

Blockade Runners.

“. . . I am only speaking of those who go to Memphis, that renowned place where our fair ladies go to take the oath of allegiance to their particular friend and protector, Abe Lincoln… They are not true-hearted Southern women, but ladies who cannot wear “Dixie Silk,” that is, the noble and patriotic homespun, but must have the finest and best their favorite city (Memphis) affords. . . I have several times been laughed at and made the subject of rude remarks by the hopeful daughters of two of our fair town ladies (who are noted for going to Memphis and wearing Yankee finery) because I had on patriotic homespun. . .” [37]

The Memphis Daily Appeal included an article in February 1864. . . “You who, in the first flush of your patriotism, gave twenty five and thirty dollars for homespuns and ostentatiously wore them, do not now discard them because they wash badly and cost so much…”[38]

Again in Georgia, 1863 as published in the Richmond Sentinel:

“Messrs. Editors:

…In Atlanta and Macon the ladies dress as in times of peace, have an abundance of fine clothes, and ride in fine carriages, drawn by fat, sleek horses. Fine bonnets and silk dresses are as thick as blackberries. Homespun by the city ladies is not much worn. It is not becoming, they say, and gives them rather a plebeian appearance.“[39]

In Savannah the Republican published in 1863:

“Where are all the ladies who, when the war broke out, were going to wear nothing but homespun during the war?—Augusta Constitutionalist.

“They are wearing out their old summer dresses, to be sure. You would not expect them to wear heavy homespun with the thermometer up in the nineties.—Mobile Advertiser.

“A still better reason is that calico is cheaper than homespun, besides being more comely. Our observation teaches that homespun is about the dearest every-day dress a lady can wear, and having had to foot several bills in that line, it has cured us completely on the subject of domestic manufactures for ladies’ dresses. What with trimming to make them look decent, the fading after the first introduction to the washtub and consequent early abandonment, it is poor economy to indulge in homespun dresses.”

Celine Fremaux remembers in Louisiana: “Later some of the neighbors called—Mrs. Wiley, Mrs. Cross, Miss Perry, etc. All were pretty women and were dressed in silk dresses protected by aprons, small, fancy aprons. Grown people’s nice clothes lasted pretty well the four years. With children it was different, we grew out of them.”[40]

Necessity

But by late 1862, many civilians were beginning to turn back to homespun out of necessity, as the blockade cleared off the merchants’ shelves and the Confederate army consumed much of what came out of Southern textile mills. Eventually, even the Alabama girls with the Valenciennes lace “really had to make it at home and wear it.”

A Soldier’s Wife wrote to the Mobile Register and Advertiser in 1863

“. . . We would make it convenient to close the doors of these extortioners in goods as well as everything else; the blockade goods do a poor man’s family no good whatever. They have not enough money to buy a yard, to say nothing of a bolt of calico, domestic, or any other kind of goods. . . This thing has to stop. . . .”

In September 1864 Sarah Watkins wrote:

“If it [the war] lasts much longer I do not know what Baby and I am to do for clothes. We are both very needy. Some people run the blockade and get things. I believe your Pa would go in rags before he would trade with the enemy. I could not go in their lines but if I had money or cotton and could get the chance, I would supply myself with clothes.”[41]

Agnes wrote from Richmond in January 1863 “Do you realize the fact that we shall soon be without a stitch of clothes? There is not a bonnet for sale in Richmond. Some of the girls smuggle them, which I for one consider in the worst possible taste, to say the least. We have no right at this time to dress better than our neighbors, and besides, the soldiers need every cent of our money. . . Heaven knows I would costume myself in coffee-bags if that would help, but having no coffee, where could I get the bags?”[42]

Some women stocked up but wanted homespun to save the better dresses “I dont [sic] need them until next winter, as I bought several calico dresses last winter & those with what I had will do me all this & next year, with care; but I wanted some homespun dresses to wear about home to save my others; as there is not a yard of calico, gingham’s, or anything else in Cam[den], except berage or swiss &cc.” wrote a woman from Arkansas in 1862.[43]

Kate Stone refugeed from Louisiana to Texas; she did everything in her power to not resort to homespun, but then in May 1864 she wrote:

“We are at last using homespun. Hemmed a dozen towels today, looking much like the dish towels of old. Little Sister is to have an outfit from the same piece, but she quite glories in the idea of wearing homespun and coming out a regular Texan.”[44]

Harriet Perry felt very strongly about using homespun as she wrote to her husband in Feb. 1864, “You spoke of a suit Lt. Dukes had & expressed a wish for some like it and said you thought it better taste to wear home made goods—it is cheaper for you to wear any other kind and I know it looks better than the homespun—the latter is so smutty and dirty I do not like it.”[45]

Homespun in living history

So when would homespun be appropriate when interpreting a person living in the Civil War South? You were most likely to wear homespun if:

- You lived in a rural, mountainous or piney woods area

- You were in Confederate held territory

- You were not near major textile weaving mills, although you may be near yarn mills or carding machines

- You were not near Union states in which friends or relatives live who can smuggle goods to you

- You were either poor, yeoman class, or enslaved

- You were male

- You were a growing, active child

- You were an ardent secessionist woman, in which case you may have worn fashionable homespun dresses beginning in 1860

- You had always made homespun, you remembered how to make homespun, or you knew someone who knew how to make homespun, whether that person was poorer, older, or an enslaved person

- You were regularly involved in physical labor, including cooking, washing, or gardening, where sturdier clothing is desirable

- It is winter 1862/1863 or later

- It is fall through early spring when it is cold, since most homespun is usually heavier than factory cloth

- You had a moral or ethical problem dealing with Yankees, either directly or indirectly, except for medical or military necessities

- You had a moral or ethical problem dealing with blockade runners, except for medical or military necessities

Drew Gilpin Faust writes in Mothers of Invention:

The homespun revolution so heralded in the postwar accounts of white southern women’s wartime achievements seems to have been actually of very limited scope. A recent study and museum exhibition entitled Mississippi Homespun: Nineteenth Century Textiles and the Women Who Made Them came to a conclusion that might be generalized to the entire South: “The oft-reported surge in spinning and weaving by women on the homefront during the Civil War was not reflected” in the surviving evidence from Mississippi. Women who had actively engaged in textile production before the war continued to do so; households where slaves had produced cloth before the war maintained or even increased their output; some women who had never spun or woven made efforts to produce fabrics, but their contributions did not have a significant impact in meeting the demand for textiles in the Confederacy. … Less fortunate southerners made do by recycling bed or table linens, curtains, and discarded garments. Economic pressures on Confederate households did not result in profound or widespread alterations in white women’s relationship to home textile production.

It is very striking how many extant references to large-scale involvement in textile production come from memoirs written after the war. Sources from the war period itself are more likely to document the difficulty and struggle in acquiring skills, raw materials, and the motivation for such efforts.

[1] https://www.sos.tn.gov/products/tsla/tennessee-civil-war-veterans-questionnaires

[2] Fleming, Mary Love Edwards. “Dale County and Its People During the Civil War” Alabama Historical Quarterly 19 (1957): 61-109.

[3] Cumming, Kate. Kate: The Journal of a Confederate Nurse. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1959, 1987 reprint, p. 64. Location: Ringgold, GA, September 8, 1862

[4] Johansson, M. Jane, ed. Widows by the Thousand: The Civil War Letters of Theophilus and Harriet Perry, 1862-1864. Fayetteville: The University of Arkansas Press, 2000, p. 28. Location: Marshall, Texas, September 15, 1862.

[5] Ibid, p. 103. Location: Harrison, Co., Texas, February 19, 1863.

[6] Ibid, p. 116. Location: Texas, undated letter

[7] http://apps.uttyler.edu/vbetts/furr_homespun_dress.htm

[8] Mills, Betty J. Calico Chronicle: Texas Women and Their Fashions, 1830-1910. Lubbock: Texas Tech Press, 1985, p. 19.

[9]Quoted in Wiley, Bell Irvin. The Plain People of the Confederacy. Gloucester, MA: Peter Smith, 1971, p. 49.

[10] Diary of Fannie Brown, 1861, 1863-1864, Rusk County, Texas

[11] Johansson. P. 41. Location: Marshall, Texas, September 24, 1862.

[12] M. J. Pierson, Lamar County, TX, to Mrs. Winstead, November 21, 1863. Pierson, M. J. Letters. Texas State Archives, Austin, Texas.

[13] Southern Illustrated News, November 8, 1862

[14] Dallas Herald, February 8, 1860, p. 1, c. 6

[15] Hay, Elzey. “Dress Under Difficulties; or, Passages from the Blockade Experience of Rebel Women.”

Godey’s Lady’s Book and Magazine 73 (July, 1866): 32-37. Contributed by Jan Stofferna to Citizens’ Companion 8 no. 5 (December 2001-January 2002): 30-37.

[16] Seabury, Caroline. The Diary of Caroline Seabury, 1854-1863. Edited by Suzanne L. Bunkers. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 1991, p. 91. Location: between Chickasaw and Island no. 40 or Buck Island on the Mississippi, July 30, 1863.

[17] Saxon, Elizabeth Lyle. A Southern Woman’s War Time Reminiscences: Electronic Edition. http://docsouth.unc.edu/fpn/saxon/saxon.html, p. 18

[18] Clara Dunlap, Ouachita County, Arkansas, to Clarissa Dickson, May 23, 1862, in Sisters, Seeds, & Cedars: Rediscovering Nineteenth-Century Life Through Correspondence from Rural Arkansas and Alabama. Edited by Sarah M. Fountain. Conway, AR: UCA Press, 1995, p. 129.

[19] Clayton, Sarah Conley. Requiem for a Lost City: A Memoir of Civil War Atlanta and the Old South. Macon, GA: Mercer University Press, 1999, p. 30.

[20] Ibid

[21] Natchez Daily Courier, October 16, 1861, p. 1, c. 2

[22] Ibid

[23] Candler, Myrtie Long, “Reminiscences of Life in Georgia During the 1850s and 1860s,” Georgia Historical Quarterly 33 no. 3 (September 1949): 227.

[24] Charleston Mercury, 20 November 1860, p. 1, c. 3, repeated in Daily Chronicle & Sentinel [Augusta, GA], 27 November 1860, p. 3, c. 2

[25] Columbus [GA] Times, quoted in the Daily Chronicle & Sentinel [Augusta, GA], 2 December 1860, p. 2, c. 1.

[26] Charleston Mercury, 6 February 1861, p. 4, c. 4.

[27] Atlanta Locomotive, quoted in San Antonio Ledger, 19 July 1861 (second quotation).

[28] Southern Confederacy [Atlanta, GA], 25 August 1861, p. 3, c. 1

[29] Charleston Courier quoted in the Natchez Daily Courier, 2 October 1861, p. 1, c. 3.

[30] Milledgeville [GA] Union, quoted in the Memphis Daily Appeal, 30 January 1861, p. 2, c. 6

[31] Marshall Texas Republican, 20 April 1861, p. 3, c. 3

[32] Albany [GA] Patriot, 21 March 1861, p. 3, c. 1

[33] Southern Confederacy [Atlanta], 27 September 1861, p. 2, c. 1-2

[34] Elizabeth Lyle Saxon, A Southern Woman’s War-Time Reminiscences. Memphis: Pilcher Printing co., 1905, pp. 18, 22, accessed 28 July 2002, http://sunsite.unc.edu/docsouth/saxon/saxon.htm.

[35] Irwin, John Rice. A People and Their Quilts. Exton, PA: Schiffer Publishing Ltd., 1984, p. 19.

[36] Fannie Baylor to Virginia King, March 23, 1863, as quoted in Bell Irvin Wiley, Confederate Women. New York: Barnes & Noble, 1994, pp. 168-169.

[37] Mobile Register and Advertiser, July 16, 1864, p. 1, c. 8

[38] Columbus [GA] Enquirer quoted in Memphis Daily Appeal [Atlanta, GA], 6 February 1864, p. 2, c. 6

[39] Southern Confederacy [Atlanta, GA], April 10, 1863, p. 1, c. 3-4

[40] Garcia, Celine Fremaux. Celine: Remembering Louisiana, 1850-1871. Edited by Patrick J. Geary. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1987, p. 105.

[41] Sarah E. Watkins, Winona, MS to Mrs. L. A. Walton, in Dimond, E. Grey and Herman Hattaway, eds. Letters from Forest Place: A Plantation Family’s Correspondence, 1846-1861. Jackson: MS: University Press of Mississippi, 1993, pp. 322-323.

[42] “Agnes”, Richmond, VA to Mrs. Richard A. Pryor, January 7, 1863, in Pryor, Mrs. Roger A. Reminiscences of Peace and War. Rev. ed. New York: Grosset & Dunlap, 1908. Reprint ed. Freeport, NY: Books for Libraries Press, 1970, p. 266.

[43] Ouachita County, AR, August 16, 1862, in Sisters, Seeds, & Cedars: Rediscovering Nineteenth-Century Life Through Correspondence from Rural Arkansas and Alabama. Edited by Sarah M. Fountain. Conway, AR: UCA Press, 1995, p. 140.

[44] Holmes, Sarah Katherine Stone. Brokenburn: The Journal of Kate Stone, 1861-1868. Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University, 1955, 1972, 1995, p. 286.

[45] Johansson. p. 219

You can also see a different version of this presentation on the Presentation page.