When the war started, the number of runaway slaves began to increase; this continued through 1864. Those in south Texas along the Mexican border were assisted by the Mexican population. Jacob Branch, a former slave, relates: “After war started, lots of slaves ran off to get to the Yankees. All them in this part headed for the Rio Grande River. The Mexicans rigged up flat boats out in the middle of the river, tied stakes with rope. When the colored people got to the rope they could pull themselves across the rest of the way on those boats.”1

When the war started, the number of runaway slaves began to increase; this continued through 1864. Those in south Texas along the Mexican border were assisted by the Mexican population. Jacob Branch, a former slave, relates: “After war started, lots of slaves ran off to get to the Yankees. All them in this part headed for the Rio Grande River. The Mexicans rigged up flat boats out in the middle of the river, tied stakes with rope. When the colored people got to the rope they could pull themselves across the rest of the way on those boats.”1

During Federal occupation of Galveston runaway slaves were not treated as contraband of war. Instead they were considered chattel who could return to their owners if they wished to continue lives as slaves. This was illustrated in the Galveston Weekly News on October 22, 1862 “We understand that one of our citizens, living on the Bay, and three negroes who ran away the other day by taking a boat and going to Galveston. The owner went for them, and was told by the Federal Commander he might take them away with their consent, but not without. They preferred to stay, and so they are lost to the owner.”2

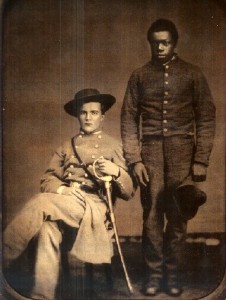

As with other southern troops, some slaves were taken to war by their owners. Thophilus Perry took his slave Norflet with him when he joined the CSA in 1862. Norflet would eventually serve a Col. Horace Randal after Randal’s slave ran away. Norflet would also run away but return home several months later. Harriet Perry wrote to Thophilus “Norflet denies running away, he says he went off to buy eggs, butter etc for Mrs. Randall and was taken up and carried to the Federals by the Jay Hawkers…”3

As with other southern troops, some slaves were taken to war by their owners. Thophilus Perry took his slave Norflet with him when he joined the CSA in 1862. Norflet would eventually serve a Col. Horace Randal after Randal’s slave ran away. Norflet would also run away but return home several months later. Harriet Perry wrote to Thophilus “Norflet denies running away, he says he went off to buy eggs, butter etc for Mrs. Randall and was taken up and carried to the Federals by the Jay Hawkers…”3

Slaves in Texas were often taken away, not to fight but to work on the protection of the Texas gulf. The CSA authorized impressments of slaves in 1863 for periods of sixty days of public service at a rate of fifteen dollars a month. Gen. Magruder then established a Labor Bureau that impressed slaves in Texas to construct fortifications, drive cotton wagons to the Rio Grande, and build a stockade to hold federal prisoners at Camp Ford near Tyler. However, not all slaveholders cooperated with the man power request. In May of 1863, Lt. Col. Freemantle wrote “…he was going with a troop of cavalry to impress one-fourth of the negroes on the plantations for the Government works at Galveston, the planters having been backward in coming forward with their darkies.”4

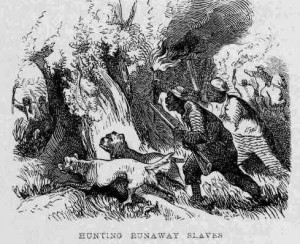

Elizabeth Neblett had other ideas “I have been thinking it would be a good plan to handcuff him [Sam, a slave] and send him to work on the fortifications on Galveston Island….If he was fed on bread & water for a while and whiped several times it might do him some good. If he should run away I would send after Colemen & his dogs without delay. If he ever comes to you and tells you he will run away…send at once for Coleman & his dogs or have him taken in custody if he has to be killed in doing so.”5

Elizabeth Neblett had other ideas “I have been thinking it would be a good plan to handcuff him [Sam, a slave] and send him to work on the fortifications on Galveston Island….If he was fed on bread & water for a while and whiped several times it might do him some good. If he should run away I would send after Colemen & his dogs without delay. If he ever comes to you and tells you he will run away…send at once for Coleman & his dogs or have him taken in custody if he has to be killed in doing so.”5

Many of the impressed slaves did run away, it was assumed, back to their masters. This motivated Gen. Magruder to threaten slave owners that if runaway slaves were not immediately returned, double the number would be required.

For those slaves who remained on the farms, their experiences varied greatly. James Hayes of Shelby Co and Andrew Goodman of Smith County both stated they did not know or were never told what the war was about. Felix Hayward of Bexar County stated “The war wasn’t so great as folks suppose…The ranch went on just like it always had before the war…Nothing was different.”6

Unfortunately, others received the brunt of their owners’ fears and frustrations during the war. Some, like Andy Anderson of Williamson County, had their food reduced. Others suffered beatings because “Your master’s out fighting and losing blood trying to save you from them Yankees, so you kin git your’n here.”7

Even with the war, the decrease in available cash and the increasing number of slaves escaping from their masters, white Texans continued to purchase slaves and offer rewards for the return of runaway slaves up to the last months of the war.

1 Tyler, Ron and Lawrence R Murphy, eds. The Slave Narratives of Texas. State House Press, Austin, 1997, page 101

2 Galveston Weekly News. October 22, 1862, page 1 column 1

3 Johansson, M. Jane. Widows by the Thousand: The Civil War Letters of Theophilus and Harriet Perry 1862-1864. Unversity of Arkansas Press, 2000, page 184

4 Fremantle, Lt. Col. Arthur J.L. Three Months in the Southern States: April – June 1863. University of Nebraska Press, 1991, page 73

5 Murr, Erika L. A Rebel Wife in Texas: The Diary and Letters of Elizabeth Scott Neblett 1852-1864. Louisiana State University Press, Baton Rouge, 2001, page 227

6 Tyler, page 112

7 Baker, Lindsay and Julie P. Till Freedom Cried Out: Memories of Texas Slave Life. Texas A&M University Press, College Station, 1997, page 85